📚 INTRODUCTION

One Shabbos afternoon in Camp Munk during the summer of 1976, a child suffered a head injury, and the camp driver was summoned to take him to the local hospital for treatment. As staff members carefully settled the child into the car, Rabbi Dovid Cohen, shlit״a, who served as the rabbinic authority for Camp Munk, calmly and decisively provided the driver with the necessary Shabbos-related halachic guidance.

The following week, Reb Dovid announced that his regularly scheduled Shabbos afternoon shiur would be devoted to explaining why he had given those specific instructions, and what had gone through his mind as he made those weighty decisions.

It was profoundly moving to sit and listen as he effortlessly wove together so many strands of Torah—sources from Gemara, halacha, and teshuvos—along with what he had heard from the leading Gedolim of that time, and what those Gedolim themselves had received from their rebbeim and from seforim of earlier generations.

At that point in my life, I had not yet found my footing in Gemara learning, and much of Reb Dovid's extraordinary shiur was beyond me. And yet, nearly fifty years later, I can still see myself sitting there, filled with awe and admiration, wondering how many lifetimes Reb Dovid must have lived to have learned, internalized, and retained so much Torah—and to have been able to draw upon it all on a moment's notice just the Shabbos before.

More than anything else, I remain deeply grateful to Reb Dovid for allowing us into his thought process that afternoon—for showing us, not just telling us, how a posek thinks; how Torah is carried with humility and responsibility; and how a lifetime of faithful learning is brought to bear when it matters most. In that moment, something deep in my relationship with Gemara quietly shifted. Not because I suddenly understood more, but because I had been given a precious glimpse of where it all leads. From that point on, Gemara was no longer an abstract intellectual pursuit; it was the living foundation of psak and of Jewish life.

I hope and pray that you, too, will be zoche to have rebbeim like Reb Dovid, and to moments like this—that open the heart, deepen one's connection to Torah, and reveal the beauty of our mesorah, showing how faithful, lifelong learning can illuminate and guide real life.

Yakov Horowitz

Artscroll introduction to Talmud

These pages were carefully designed to serve as a "stand-alone" resource, while simultaneously offering learners the opportunity to do a "deep dive" with extensive footnotes, many of them referencing Artscroll's "Introduction to Talmud" (ITT).

(need to add something here, discuss with Gedaliah - Y.H)

🎯 THIS BOOK'S GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

In writing this sefer, it was important to state clearly what it is intended to accomplish, and to manage expectations accordingly. Its purpose may be summarized as follows:

Upon completing this sefer, the learner will have acquired the foundational skills necessary to independently learn and retain Mishnah and Gemara, with the aid of ArtScroll's Mishnah and Gemara learning tools.

Stated differently, this work is intended to serve as an entry point for learners with limited or no background in Gemara, enabling them to benefit meaningfully from its study.

This aim was shaped, in part, by a conversation with a distinguished professional who became religiously observant later in life. Years after his initial commitment, he expressed a strong desire to engage seriously in Gemara learning. He had invested considerable effort—acquiring numerous English-language Gemara editions and attending many shiurim—yet found himself unable to progress.

He observed that these excellent resources presupposed a degree of familiarity and a set of foundational skills that he had never been taught. His difficulty lay not in motivation or ability, but in the absence of an accessible starting point.

This sefer is written for learners in similar circumstances. Its goal is to establish those foundational elements that are often assumed, so that further study can proceed with clarity and confidence.

This work is offered with humility and a sense of responsibility. If it assists learners in taking their initial steps toward independent Gemara learning, it will have achieved its aim.

May you be zocheh to clarity and steadiness in learning, and may these beginnings lead to your continued growth in Torah study.

📜 THE WRITTEN TORAH AND THE ORAL TORAH

At Har Sinai, Hashem gave Moshe Rabbeinu the Torah in two inseparable forms: the Written Torah (Torah Shebiksav) and the Oral Torah (Torah Sheb'al Peh). Each was given to fulfill a distinct and complementary role in the transmission of the Torah and its observance.

The Written Torah

The Written Torah consists of the Five Books of the Torah given to Moshe Rabbeinu at Har Sinai. It presents the mitzvos and teachings of the Torah in precise and deliberately concise language, often without detailing the manner of their practical fulfillment.

This concision is intentional. The Written Torah establishes the authoritative text of Divine law, defining what Hashem commands, while frequently leaving unstated how those commands are to be carried out. Central areas of Jewish observance such as Shabbos, Tefillin, Kashrus, and ritual slaughter are mentioned explicitly, yet their correct observance cannot be derived from the written text alone.

By design, the Written Torah is fixed and eternal in its wording. It serves as the immutable foundation of Jewish law. At the same time, its brevity necessitates an accompanying explanatory tradition, through which its meaning is preserved and its application ensured in every generation.

The "Big Picture" Analogy

Consider a job interview scenario: when a shul is hiring someone to supervise children during services, an employer doesn't outline every single detail during the initial conversation. Instead, they provide the big picture - supervise the children, keep things interesting, allow parents to pray without being disturbed - and work out the specifics later.

The Written Torah functions similarly. It presents the big picture. Opening a Chumash reveals that all the complicated rules of tefillin or Shabbos are condensed into just a few verses.

For example: "Remember the day of Shabbos and keep it holy. You work for six days; the seventh day you rest." - Shemos (Exodus) 20:8-10

Gedaliah, should we add more sources for pesukim?

Where are all the detailed laws? What constitutes "work"? What about electricity, which didn't exist in biblical times? These details exist in the Oral Torah - the Mishnah and Gemara - which provides the explanatory framework for understanding and applying the Written Torah's principles.

The Oral Torah

The Oral Torah preserves the authoritative explanation of the Written Torah as transmitted from Moshe Rabbeinu onward. Through it, the meaning, scope, and practical application of the Written Torah were conveyed faithfully from teacher to disciple across generations.

As noted above, Hashem gave Moshe both the Written Torah and the Oral Torah during his forty days on Har Sinai. The voluminous content of the Oral Torah was conveyed faithfully from Moshe Rabbeinu to his disciple Yehoshua, beginning an uninterrupted chain of Mesorah that continued for thirty-four generations.

During the period of the Second Beis HaMikdash, however, the disruption and upheaval brought about by Roman occupation threatened the integrity of this transmission.

(For an outstanding, in-depth treatment of the history of that period in Eretz Yisrael and Babylonia, see ITT pages 53-97.

Gedaliah, should we add more footnotes for ITT?)

At that juncture, Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi citing the verse "eis la'asos La'Shem..." took the unprecedented step of committing the Oral Torah to writing. He gathered the sages of his generation and compiled the Mishnah, a concise written record of the Oral Torah, in order to preserve it for future generations. Although committed to writing, it continued to be regarded as part of the Oral Torah.

In later generations, motivated by similar concerns, the sages recorded the Gemara as well.

The Structure of the Mishnah: Six Sedarim

Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi organized the Mishnah into six books, or orders, called Shisha Sidrei Mishnah - this is where the word "Shas" comes from. The broad categories are:

- Zeraim (Seeds): All halachos related to planting, crops in Eretz Yisrael, giving to Kohen, Levi, and poor people. Anything related to the cycle of working the fields and producing crops.

- Moed (Appointed Times): Holidays, like Chol HaMoed, Yom Tov, and the halachos of Yom Tov and Shabbos.

- Nashim (Women): Basically marriage and divorce - Gittin, Kiddushin, Yevamos.

- Nezikin (Damages): Tort law and damages. This occupies a very big part of Gemara learning.

- Kodshim (Holy Things): Things relating to Karbanos and how they are brought. Challenging material, mostly applicable during the time of the Beis Hamikdash.

- Taharos (Purities): Rules of Tumah and Tahara, ritual purity.

Each Seder is divided into Masechtot (tractates), then into Perakim (chapters), and then individual Mishnayos

(Reb Yehudah Hanasi did a remarkable job of pulling together all the oral teachings and making a user-friendly “filing system”

so that learners could access all the information he committed to writing.

In the vernacular, it is similar to the way we organize the folders and sub folders in our PC’s).

Why the Torah was transmitted in both written and oral forms

- The scope of the Oral Torah is vast. Its full content could not be committed to writing without loss of clarity or precision.

- The Torah was given to guide Jewish life in every generation. Accordingly, Moshe was taught not only the particulars of the laws, but also their governing principles, so that they could be applied faithfully to circumstances that would arise over time.

- Rambam explains that written texts are susceptible to misunderstanding when read without sufficient mastery of the subject. Preserving a substantial portion of the Torah through direct transmission from teacher to disciple ensured greater accuracy and continuity in its preservation.

Sources supporting the existence of the Oral Torah

- The Toras Kohanim in Parshas Bechukosai draws attention to the verse that speaks of "the Torahs" in the plural that Hashem gave to the Children of Israel at Har Sinai through Moshe. The use of the plural form indicates that more than one body of Torah was given: the Written Torah together with the Oral Torah.

- The Written Torah itself contains references that point to an additional explanatory body of law. One such example appears in the laws of ritual slaughter, where the Torah states in the voice of Hashem, "You shall slaughter ... as I have commanded you." Since the detailed laws of shechita are not recorded in the Written Torah, it follows that they must have been transmitted orally.

- Many complex areas of Halacha such as those of Tefillin and Shabbos are mentioned only briefly in the Written Torah, often in just a few verses. Without an accompanying Oral Torah to explain and elaborate upon their details, large portions of the Written Torah would be impossible to understand or observe in practice.

An Analogy: The Computer Repairman

YH. Discuss “the IT guy” analogy with Gedaliah

📖 MISHNAH AND GEMARA

The Mishnah and the Gemara serve different purposes, and they are meant to feel different when you learn them.

The Mishnah tells you what Jewish law is. It presents the basic rules and categories in a short, direct style. It does not explain where the rules come from or how they were worked out. It assumes that background already exists and simply states the results. Because of this, the Mishnah can feel brief, orderly, and sometimes hard to unpack.

The Gemara comes afterward and explains the Mishnah. It asks simple but important questions: Why does the Mishnah say this? How do we know it is correct? What happens in related or unclear cases? The Gemara brings discussions, disagreements, examples, and real-life situations that help clarify how the law works. It shows the thinking process behind the rules, not just the rules themselves.

Learning Mishnah often feels neat and structured. Learning Gemara can feel challenging, and at times even confusing, because it does not move in a straight line. But that challenge is intentional. The Gemara is training the learner how to think about halacha, not just how to remember it.

A helpful way to think about it is this: the Mishnah gives you the final answer, while the Gemara shows you how that answer was reached.

Here are two everyday examples that may help:

1. Meeting notes vs. the discussion

If you missed an important meeting, reading the meeting notes would tell you what decisions were made. But if you could listen to the full discussion, you would understand much more—what questions were raised, what concerns came up, and why certain choices were made. The Mishnah is like the notes. The Gemara is like hearing the discussion itself.

2. A referee's call

When a referee makes a call in a game, you hear the decision right away. But when a commentator explains why the call was made, what the rules are and how they apply, you gain a much deeper understanding. If two commentators then debate the call, you learn even more. That kind of explanation and discussion is what the Gemara provides.

In short, the Mishnah gives you the structure of Jewish law, and the Gemara brings it to life by showing how it is understood, debated, and applied.

🧠 THE IMPORTANCE OF FOLLOWING THE LOGICAL FLOW OF THE GEMARA

In September 1997, I was in an Israeli taxi listening to the radio, where a reporter was interviewing Rabbi Michel Zilber, one of the most prolific Gemara (Talmud) teachers of that generation. Having served as an eighth-grade Gemara rebbi (teacher) for fifteen years at that time, my ears perked up when the reporter asked the rabbi, "Were you at the top of your Gemara class in your formative years?" Rabbi Zilber responded, "No, I was quite average in ability and achievement. But after every Gemara class I attended, I carefully broke down the logical flow of the Gemara's give and take (shakla v'tarya), identified each step, and committed it to paper before I moved ahead to the next Gemara segment."

A man walks home from shul with his son and tells him we are having hamburgers for supper.

On the way, the son asks, "How do you know we are having hamburgers?" The father answers, "I saw your mother defrosting chopped meat." The son responds, "Maybe she is making meat loaf." The father replies, "That is possible. But I also saw her place hamburger buns right next to the meat."

I imagine that Rabbi Zilber would correctly disassemble the conversation above into five logical components, using the same terminology that appears throughout the Gemara as presented by ArtScroll

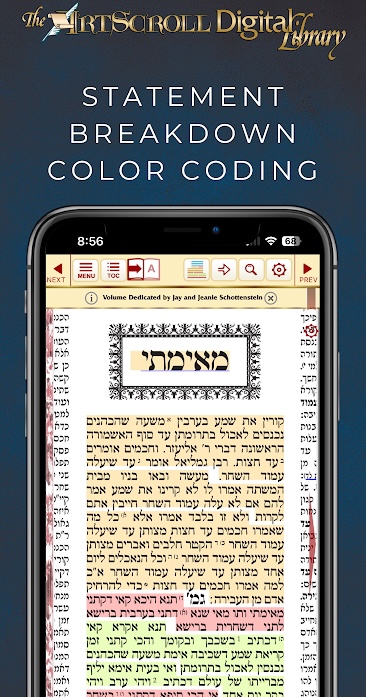

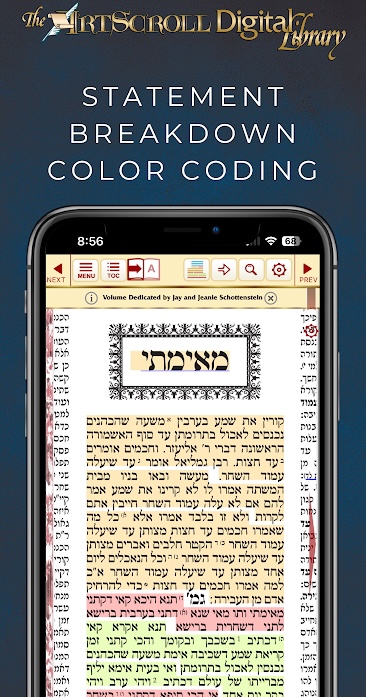

(please note: colors being used match factory default settings in the mobile app steps breakdown - see below "Key to Gemara's Logical Steps"):

1

Statement

"We are having hamburgers for supper."

2

Question

"How do we know that supper will be hamburgers?"

3

Answer

"Mom is defrosting chopped meat."

4

Inquiry

"Perhaps the chopped meat is for meat loaf and does not prove we are having hamburgers."

5

Proof

"She also placed hamburger buns right next to the meat."

Carefully following and identifying the logical steps of discussions in Gemara is crucial for several reasons. The debates that take place in Gemara are not only about arriving at a conclusion (maskana), but also about understanding the reasoning (svara) and methodology behind the decisions. By following the logical steps of these discussions, one can better appreciate the nuances and depth of how our chachamim (sages) thought. The Gemara often employs intricate discussions, and missing a single step or misunderstanding a key argument can result in an underdeveloped understanding of the issue being addressed.

Furthermore, Gemara learning is characterized by its structured analytical approach. A statement is presented, a question is raised, an answer is offered, that answer is examined through inquiry, and finally a proof is brought to establish or reject it. This process is designed to sharpen one's thinking and to encourage careful examination of every assumption and position. Identifying the logical progression of each debate helps track the development of the discussion, which often involves contrasting opinions, qualifications, and apparent contradictions that are resolved through careful reasoning. By grasping this logical flow, learners can gain a deeper insight into how Halacha (Jewish law) evolves over time.

Moreover, careful attention to the logical steps ensures that one can engage in meaningful interpretation and application of the Gemara—which is much more than just a historical record but a living document that continues to inform contemporary Jewish practice. Understanding how our chachamim arrived at their conclusions allows for a more informed and reasoned application of these principles—and Halacha overall—to modern developments, like scientific and technological advances.

Applying this to the opening Mishnah of Berachos

This logical structure can be seen clearly in the very opening Mishnah of Maseches Berachos. The Mishnah presents the issue of the nighttime recitation of Krias Shema:

"From when may one recite Krias Shema (the central biblical declaration of Jewish faith) at night?"

It then provides a ruling:

"From the time the kohanim (priests) enter to eat their teruma (the sanctified food given to priests)."

Someone trained in the Gemara's method would naturally break this Mishnah into the same logical steps:

1

Statement

There is a defined time at which the nighttime obligation of Krias Shema begins.

2

Question

"From when may one recite Krias Shema at night?"

3

Answer

"From the time the kohanim enter to eat their teruma."

4

Inquiry

Is this time mentioned in order to define the beginning of halachic night for Shema, or is it cited only because it relates to the laws of ritual purity that govern when kohanim may eat teruma?

5

Proof

The Gemara analyzes the relevant verses and halachic framework and establishes that the time when kohanim may eat teruma corresponds to the onset of halachic night, thereby defining the beginning of the obligation to recite Krias Shema.

💡 ARTSCROLL'S GEMARA TRANSLATION AS A "CONTEXT WHISPERER"

About forty years ago, when I was just beginning my career teaching Gemara, I once drove four businessmen to the airport, all of them in the floor-covering industry. For the entire hour they spoke nonstop "shop talk"—technical terms, shorthand, references to things obvious to them but meaningless to an outsider. I sat there completely lost.

When I dropped them off, it suddenly struck me: this is exactly how many beginners feel when they open a Gemara. We speak in "insider language," assuming background, logic structures, and unspoken steps that they simply don't have yet. Without someone quietly explaining what's really going on, they're shut out of the conversation.

That experience changed how I taught. I realized the learner doesn't just need translation—he needs a gentle companion who whispers the missing pieces, explains what the Gemara means, and guides him through the back-and-forth. And that's precisely what Artscroll's English Gemara does so brilliantly. The bold text gives you what the Gemara says. The regular text is the whisperer in your ear, filling in assumptions, clarifying the flow, and helping you feel like you're inside the sugya instead of listening from the hallway.

When translation isn't enough

Imagine our married daughter sends me to the grocery store. She texts a simple list:

- Milk

- Cheese

- Chicken

- Yogurt

Sounds easy, right? Except... it isn't.

Because I don't shop regularly, she didn't factor in that I don't automatically know the "insider information" that she assumes:

So I'm standing there in the aisle, frustrated, surrounded by a thousand options, technically knowing the words on the list... but not actually knowing what to do with them. The words are clear; the meaning isn't.

That's where the "context whisperer" comes in.

A real shopping list for someone like me would look like this:

- Milk—2%, half gallon

- Cheese—shredded mozzarella

- Chicken—boneless cutlets, family pack

- Yogurt—vanilla Greek, big container

Same list. Same words. But now there's someone quietly "whispering" the missing assumptions and background that regular shoppers already know.

That's exactly what Artscroll does.

The bold text tells you the words.

The regular text whispers everything an experienced learner already knows—the background, assumptions, and context—so you're not standing in the Gemara aisle wondering which "milk" your rebbi meant.

The first five words of the first Mishnah in Berachos

- מאימתי—From when

- קורין—do they read

- את—(the direct-object marker; indicates "the")

- שמע—Shema

- בערבין—in the evenings

Even if you translate the opening line of the Mishnah perfectly:

"From when do they read the Shema in the evenings?"

you still don't actually understand anything. A beginner is flooded with unanswered questions. A raw translation gives you the words, but it doesn't give you the world behind the words. That's why a "Gemara whisperer" is needed.

Here are the kinds of questions a normal learner immediately has:

- What is "Shema"? A single pasuk? A paragraph? Something ritual? Something halachic?

- Who is "they"? Kohanim? All Jews? Only men? Only when davening?

- What does "read" mean? Out loud? Quietly? From a siddur? By heart?

- Why evenings specifically? What changed at night? Why not morning first?

- Why is timing even a halachic issue? What happens if someone says it earlier or later?

- What mitzvah are we actually dealing with? Torah obligation? Rabbinic? Custom?

- What background is assumed? Krias Shema, mitzvos tied to day/night, Kohanim schedules, Beis HaMikdash framework, tuma/tahara context, etc.

None of that is in the words.

All of that lives in the background knowledge that Chazal assumed their readers already had.

That's why a "Gemara whisperer" is essential—whether it's a rebbi or Artscroll. The bold words tell you what the Gemara says. The whisperer quietly supplies everything the text leaves unstated: the halachic world, the assumptions, who's speaking, what problem is being solved, and why this matters. Without that, you're technically "reading," but practically locked out of understanding.

📚 GUIDE TO USING AN ARTSCROLL GEMARA

The Artscroll Schottenstein Talmud is one of the most widely used English translations of the Babylonian Talmud. Beyond simple translation, Artscroll provides learners with an extensive array of tools designed to give readers the background information and context they need to truly comprehend both the Mishnah and Gemara. This guide will walk you through these powerful learning aids, helping you maximize your Talmud study.

Part I: Pre-Learning Background Information

Before diving into the actual text of the Talmud, Artscroll provides several layers of introductory material to orient the learner. These introductions progress from the broadest context to the most specific, ensuring the reader understands the "big picture" before engaging with individual passages.

1. The Seder (Order) Introduction

see page number X in artscroll gemara brachos

Each of the six Orders (Sedarim) of the Mishnah begins with a comprehensive introduction. For example, the introduction to Seder Zera'im (the Order of Seeds) explains:

- The relationship between the Written Torah and the Oral Torah

- How the Mishnah came to be codified and its structure

- An overview of all six Orders: Zera'im (Seeds/Agriculture), Moed (Appointed Times/Festivals), Nashim (Women/Marriage), Nezikin (Damages/Torts), Kodashim (Holy Things/Sacrifices), and Tohoros (Purities)

- The meaning and etymology of key terms like "Mishnah" and "Gemara"

The Seder introduction also includes detailed footnotes (labeled "NOTES") that provide scholarly sources and deeper explanations for those who wish to explore further. These notes reference classic commentaries such as the Rambam's Introduction to the Mishnah, Tosafos Yom Tov, and other authoritative sources.

2. The Tractate (Maseches) Introduction

see page number X in artscroll gemara brachos

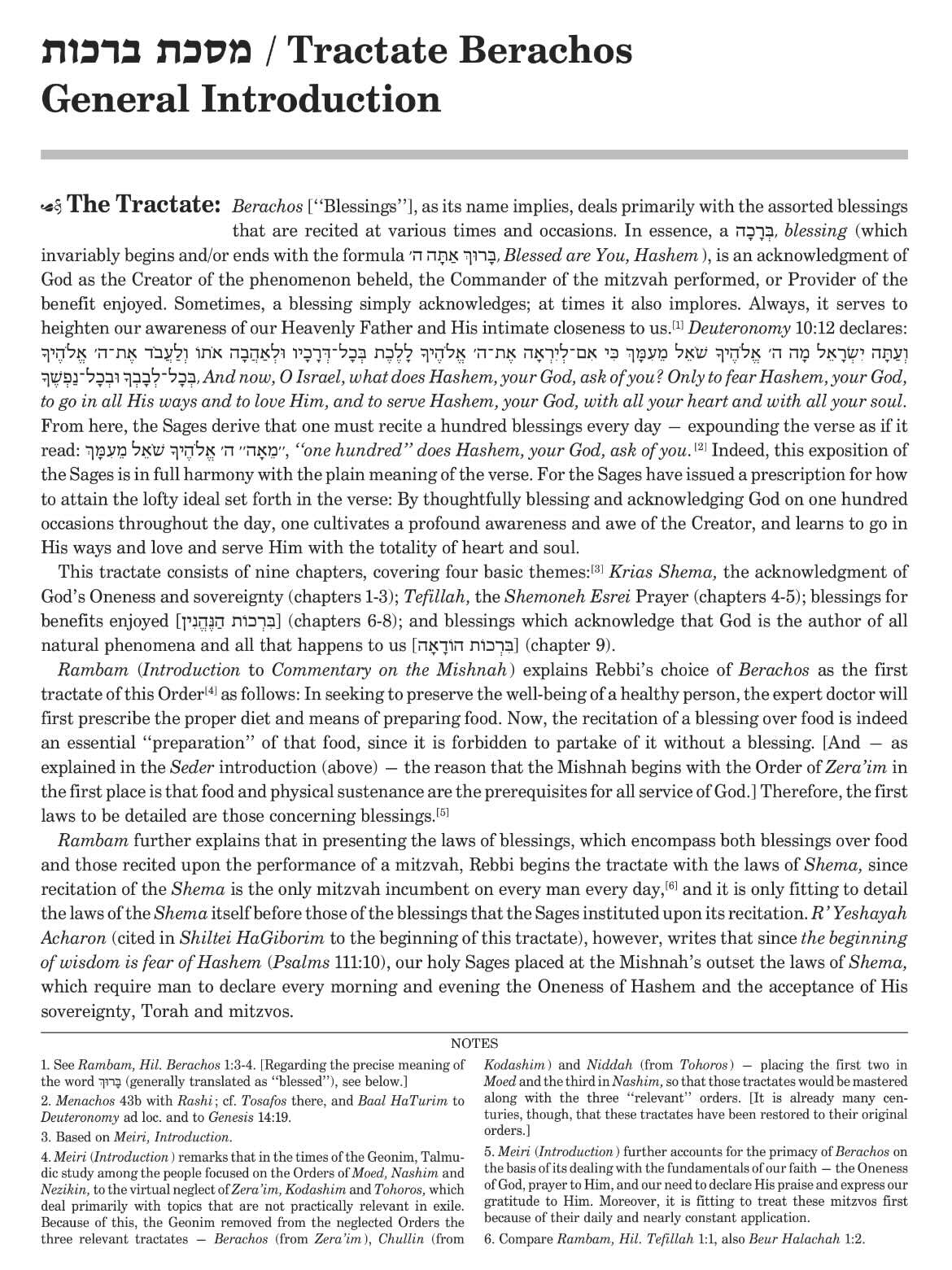

Each tractate opens with its own "General Introduction." The introduction to Tractate Berachos (Blessings), for instance, covers:

- The nature and purpose of blessings: What a beracha is, how it acknowledges God as Creator, and how blessings cultivate awareness of the Divine

- The Scriptural basis: The verse from Deuteronomy 10:12 and the Sages' derivation that one must recite one hundred blessings daily

- The tractate's structure: Berachos consists of nine chapters covering Krias Shema (chapters 1-3), Tefilla/Shemoneh Esrei (chapters 4-5), blessings for enjoyment (chapters 6-8), and blessings of acknowledgment (chapter 9)

- Why this tractate comes first: Explanations from the Rambam and other authorities about the primacy of Berachos

3. The Chapter (Perek) Introduction

see page number X in artscroll gemara brachos

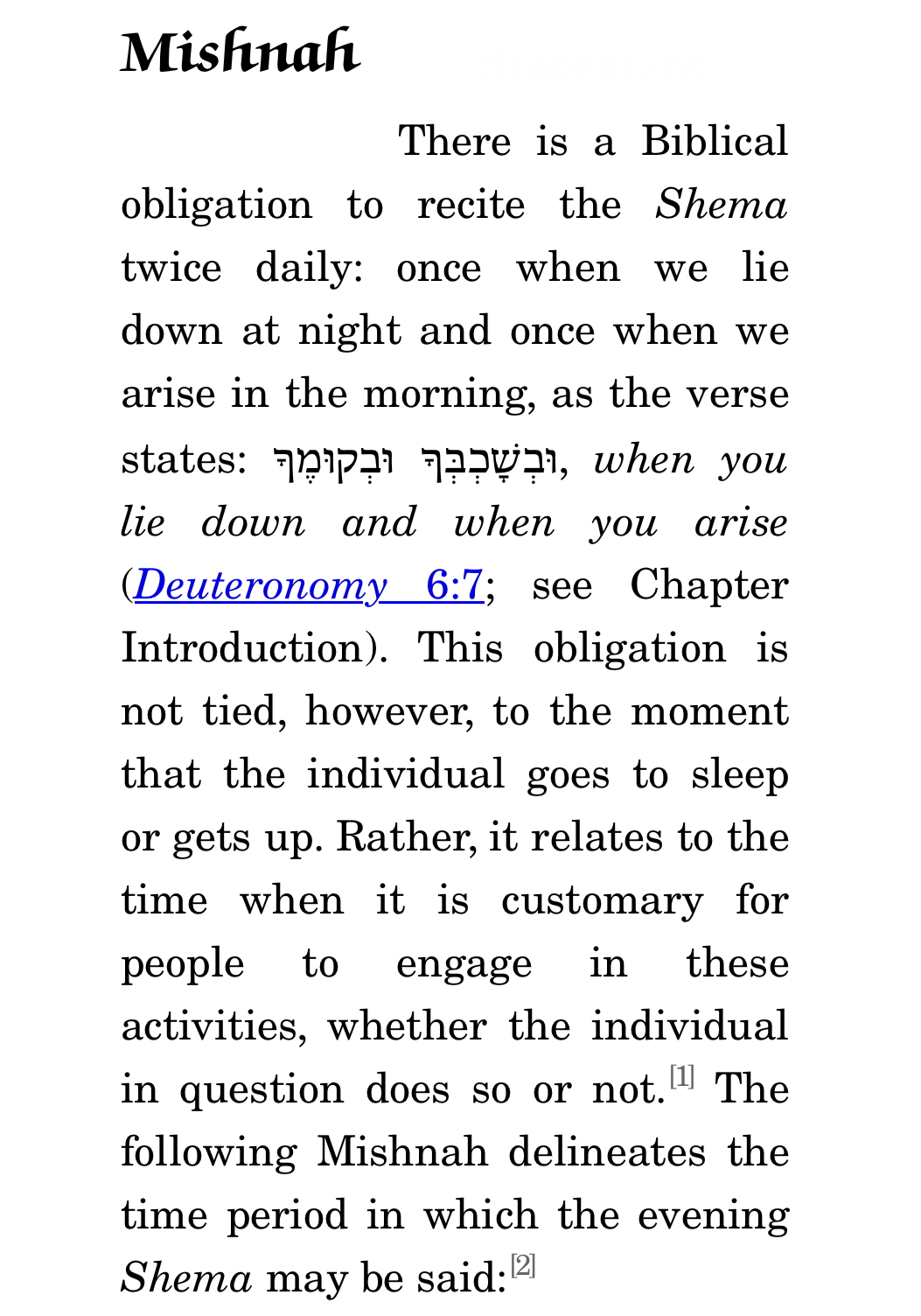

Each chapter begins with an introduction that previews the specific topics to be discussed. The Chapter One introduction in Berachos explains:

- The Biblical obligation to recite the Shema twice daily, derived from "when you lie down and when you arise" (Deuteronomy 6:7)

- The three Scriptural passages that comprise the Shema: Shema Yisrael (Deuteronomy 6:4-9), V'hayah im shamoa (Deuteronomy 11:13-21), and Vayomer (Numbers 15:37-41)

- The disputes concerning the precise times for recitation

- The blessings of the Shema (Birchos Krias Shema) and the Aggadic material interspersed throughout

4. Pre-Mishnah Introductions

see page number X in artscroll gemara brachos

Some Mishnayos have their own brief introductions that appear before the Mishnah text itself. These provide immediate context for the specific legal discussion that follows, explaining any necessary background concepts.

Part II: Tools for Active Learning

Once you begin learning the actual text, Artscroll provides several integrated features to help you understand the material.

1. The Dual-Font Translation System

The Artscroll translation uses a distinctive two-font system:

- Bold text: Represents a direct, literal translation of the Hebrew/Aramaic original. This is what the Gemara actually says.

- Regular (lighter) text: This supplementary text "whispers" into the ear of the reader, providing clarification, implied context, and explanatory words that help the reader understand what the Gemara means. These additions make the terse Talmudic language comprehensible without altering the meaning.

For example, where the Gemara tersely states "From when" (מאימתי), the Artscroll adds the explanatory text so it reads: "From when may we fulfill the obligation to recite the Shema in the evenings?" The words "may we fulfill the obligation to recite" appear in lighter font, indicating they are added for clarity.

2. Logical Structure Labels

The printed Artscroll identifies the logical flow of the Gemara's discussion by labeling key structural elements. You will see markers such as:

- "The Gemara asks:"—Introducing a question or challenge

- "The Gemara answers:"—Introducing a resolution

- "The Gemara objects:"—Introducing a contradiction or difficulty

- "The Mishnah states:" or "The master said:"—Citing authoritative sources

These labels help learners follow the back-and-forth dialectic that characterizes Talmudic reasoning.

3. The Notes Section

Below the translation text on each page, you will find a comprehensive "NOTES" section. These notes provide:

- Explanations of difficult concepts

- Background information on historical, agricultural, or Temple-related topics

- Citations of Rashi, Tosafos, and other classical commentaries

- Alternative interpretations and minority opinions

- Cross-references to related discussions elsewhere in the Talmud

The notes are numbered and correspond to superscript numbers in the translation text, allowing you to easily locate the relevant explanation.

4. The Page Numbering System

The traditional Talmud page (daf) has two sides: "a" (amud aleph, the front) and "b" (amud beis, the back). Since the Artscroll translation spreads one side of a traditional page across multiple pages, they use a superscript numbering system:

- 2a¹—First page of daf 2, side a

- 2a²—Second page of daf 2, side a

- 2a³—Third page of daf 2, side a

- 2b¹—First page of daf 2, side b

This system allows you to easily reference specific locations that correspond to the traditional Vilna edition page numbers used universally in Talmud study.

5. The Shaded Side Bar on the Gemara Text

Each Artscroll spread consists of two facing pages: one page contains the English translation with notes, and the opposite page displays the traditional Vilna Talmud layout, with the Gemara text in the center (Rashi and Tosafos commentaries surrounding it). Running along the edge of the Gemara text (not the commentaries) is a gray shaded bar that indicates exactly which portion of the Aramaic text is being translated on the facing Artscroll page.

As you flip through successive pages of the Artscroll (e.g., 2a¹, 2a², 2a³), you will notice this gray bar progressively moving down the side of the Gemara text. This visual marker allows you to see precisely which section of the original Gemara corresponds to the English translation you are reading.

For example, if you are on Artscroll translation page 2a¹ and want to locate the corresponding text in the Vilna layout, simply look at where the shaded bar appears on the Gemara text on the facing page. That highlighted section is what's being translated. This feature helps learners follow along with the traditional Talmud layout and makes it easier to transition to studying from a standard Gemara in the future.

Part III: Resources at the Back of the Book

1. The Glossary

At the back of each Artscroll Gemara volume, you will find a comprehensive glossary of Hebrew, Aramaic, and technical terms. This glossary defines concepts such as:

- Amora—A sage of the Gemara

- Baraisa—A Tannaitic teaching not included in the Mishnah

- Beis din—A Rabbinic court

- Aggadah—Non-legal, homiletical Rabbinic teachings

- Tumah/Taharah—Ritual impurity and purity

The glossary is arranged alphabetically and provides clear, concise definitions that help learners quickly look up unfamiliar terms.

2. The Scriptural Index

The Scriptural Index lists every verse from Tanach (the Hebrew Bible) that is cited or discussed in the tractate. It is organized by book—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, etc.—and provides the specific page numbers where each verse appears.

For example, if you want to find everywhere Deuteronomy 6:7 (the verse about reciting the Shema "when you lie down and when you arise") is discussed, the Scriptural Index will point you to pages 2a², 4b³, 10b¹, and so on.

This is an invaluable resource for those studying the Biblical basis of Talmudic laws or tracing how a particular verse is interpreted throughout the tractate.

Part IV: Learning Tools Outside the Printed Gemara

1. The Artscroll Mobile App

Artscroll offers a digital version of the Schottenstein Talmud through the Artscroll Digital Library app (available for iOS and Android). The app provides several features that enhance the learning experience beyond what the printed edition offers:

- Color-coded logical components: The app can automatically highlight different elements of the Gemara's discussion using colors, showing you where questions, answers, statements, proofs, and inquiries begin and end. This makes the logical flow of the Talmud even more apparent than in print.

- Translation popover: Tap on any Hebrew or Aramaic phrase and the English translation pops up directly over that phrase, allowing for quick reference without losing your place.

- Synchronized scrolling: When using the English translation and footnotes, they scroll synchronously as you scroll through the Hebrew text.

- Place tracking: The app shows you the exact corresponding place on the opposite page, so you never lose your place and always know where you are in the text.

- Hyperlinked references: Tap on a footnote or Talmudic reference and the app can bring up the referenced portion of the Talmud directly, without needing to pull out another volume.

- Searchability: Search for any word in Hebrew or English across the entire Digital Library.

- Notes, bookmarks, and highlights: Add personal notes, bookmarks, and highlights that sync across your devices.

- Portability: Access the entire Shas on your phone or tablet, with volumes available for offline use.

2. The Artscroll Stone Edition Tanach

The Gemara frequently cites and interprets Biblical verses. While Artscroll provides translations of these verses within the Gemara, having access to the Artscroll Stone Edition Tanach allows for deeper study:

- Read verses in their full context, not just as isolated citations

- Access Artscroll's commentary on the verses themselves

- Understand how traditional commentators like Rashi and Ibn Ezra interpret the pshat (plain meaning)

- Compare the Gemara's interpretation with the contextual meaning of the verse

📖 HOW TO USE A STANDARD VILNA SHAS GEMARA

Before using the Artscroll Gemara, it is helpful to understand the terminology and layout of the standard Vilna Shas, as Artscroll's format is designed to complement this traditional edition.

Key Terminology

The Talmud uses specific Hebrew and Yiddish terms for its pagination:

Daf (Hebrew, דף): Literally meaning "board" or "leaf," a daf refers to a single folio page, which has two sides. When someone says they are learning "daf 5," they mean both sides of that page.

Blatt (Yiddish, בלאַט): This is the Yiddish equivalent of daf, also meaning "leaf" or "page." You will often hear people say "today's blatt" when referring to their daily Talmud study.

Amud (Hebrew, עמוד): Literally meaning "column" or "pillar," an amud refers to one side of a daf. Each daf has two amudim.

Amud Aleph (עמוד א׳) or Side A: The front side of a daf, sometimes marked with a single dot (.) after the page number.

Amud Beis (עמוד ב׳) or Side B: The back side of a daf, sometimes marked with a colon (:) after the page number.

So when someone references "Berachos 2a," they mean Tractate Berachos, daf 2, amud aleph (the front side). "Berachos 2b" would be the back side of that same page.

Shas (ש״ס): An acronym for Shisha Sedarim, meaning "Six Orders," referring to the six divisions of the Mishnah. The term Shas is commonly used to refer to the entire Talmud.

Why Every Tractate Begins on Daf Beis (Page 2)

You may notice that every tractate of the Talmud begins on page 2, not page 1. This practice originated from early printing customs: the title page of each tractate was counted as page 1, so the first page of actual Talmudic text became page 2. This standardized pagination was established by the Christian printer Daniel Bomberg in his Venice edition (1519-1523) and has been followed ever since, allowing Jews anywhere in the world to reference the exact same page.

Some offer additional interpretations: that page 1 represents reverence for God (Yirat Hashem), reminding us that awe and humility must precede learning; or that the missing page 1 symbolizes that there is always more Torah to learn, representing what we have yet to study.

The Layout of a Standard Vilna Page

The Vilna Shas, first printed in the 1880s by the Widow Romm and Brothers of Vilna, established the layout that virtually all printed Talmuds follow today. This layout is called the tzuras hadaf (form of the page). Understanding its structure will help you navigate both the traditional Gemara and the Artscroll edition:

The Center Column

The main Talmudic text appears in the center of the page. This includes the Mishnah (the earlier, foundational law code) and the Gemara (the later rabbinical discussion and analysis of the Mishnah). A new Mishnah section is introduced with the bolded abbreviation מתני׳ (for Mishnah), while a new Gemara section begins with גמ׳ (for Gemara). The first word of each tractate is set within a decorative border.

Rashi's Commentary (Inner Margin)

On the side of the page closest to the binding, you will find the commentary of Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki (Rashi, 1040-1105). Rashi's commentary focuses on explaining the plain meaning of the text and is essential for basic comprehension. It is printed in a distinctive semi-cursive typeface known as "Rashi script."

Tosafos (Outer Margin)

On the outer edge of the page, opposite Rashi, are the Tosafos (literally "additions"). These are critical analyses written primarily by Rashi's students and descendants in 12th and 13th century France and Germany. While Rashi explains the straightforward meaning, the Tosafos raise questions, explore contradictions, and offer alternative interpretations. Tosafos are also printed in Rashi script.

Additional Marginal References

Around the main commentaries, you will find several reference tools in very small print:

- Masoret HaShas: Cross-references to parallel passages elsewhere in the Talmud, appearing near Rashi's commentary.

- Torah Or: References to Biblical verses mentioned in the text.

- Ein Mishpat Ner Mitzvah: References to later halachic (legal) codes such as the Rambam and Shulchan Aruch, showing how the Talmudic discussion was codified into practical law.

The Header

At the top of each page (from right to left), you will find the chapter name and number, the name of the tractate, and the page number (daf) with its side indicator (aleph or beis).

🔑 Key to Gemara's Logical Steps

📢 Statement

❓ Question

✓ Answer

🤔 Inquiry

📜 Proof

📋 THE MISHNAH

Note:

The mishnah translations below are copied directly from artscroll - which includes the bold and regular font

🌙 THE MISHNAH'S DISCUSSION

❓

QUESTION: When Do We Recite Evening Shema?

מֵאֵימָתַי קוֹרִין אֶת שְׁמַע בָּעֲרָבִין?

"From when may we fulfill the obligation to

recite the Shema in the evenings?"

The Opening Question: The Mishnah begins with the fundamental question about timing - when exactly does the obligation to recite the evening Shema begin?

✓

ANSWER #1: Rabbi Eliezer's Opinion

מִשָּׁעָה שֶׁהַכֹּהֲנִים נִכְנָסִים לֶאֱכוֹל בִּתְרוּמָתָן. עַד סוֹף הָאַשְׁמוּרָה הָרִאשׁוֹנָה. דִּבְרֵי רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר.

"From the time that Kohanim who were tamei

may enter to eat their teruma; i.e. at nightfall.

And one may recite the Shema until the end of the first watch;

these are the words of R' Eliezer."

Rabbi Eliezer's View:

• Start time: When Kohanim may eat teruma (when stars emerge)

• End time: End of first watch (approximately 3-4 hours into the night)

• He gives both a beginning point and an endpoint

✓

ANSWER #2: The Sages' Opinion

וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: עַד חֲצוֹת.

"But the Sages say: it may be recited until midnight."

The Sages' View:

• Start time: Same as Rabbi Eliezer (implied - when Kohanim eat)

• End time: Midnight (more generous than Rabbi Eliezer)

• They extend the time window further into the night

✓

ANSWER #3: Rabban Gamliel's Opinion

רַבָּן גַּמְלִיאֵל אוֹמֵר עַד שֶׁיַּעֲלֶה עַמּוּד הַשַּׁחַר.

"Rabban Gamliel says: It may be recited until the light

of dawn rises."

Rabban Gamliel's View:

• Start time: Same as the others (implied)

• End time: Until dawn (the most lenient opinion)

• He extends it all the way until morning begins

THREE OPINIONS ON THE DEADLINE

Rabbi Eliezer

⏰ End of 1st Watch

(~3-4 hours)

Most stringent

The Sages

⏰ Midnight

(~6 hours)

Middle position

Rabban Gamliel

⏰ Dawn

(entire night)

Most lenient

💡 Understanding the Mishnah's Structure:

Notice that all three opinions agree on when evening Shema begins (when Kohanim eat teruma), but they disagree on the deadline. The Mishnah presents three progressively more lenient views.

📖 THE MISHNAH CONTINUES: A Story

📢

STATEMENT: A Real-Life Incident

מַעֲשֶׂה וּבָאוּ בָנָיו מִבֵּית הַמִּשְׁתֶּה, אָמְרוּ לוֹ: לֹא קָרִינוּ אֶת שְׁמַע

"It once happened that [Rabban Gamliel's] sons came home after midnight

from a banquet. They said to [Rabban Gamliel]: We have not yet

recited the Shema; may we recite it now?"

The Story: Rabban Gamliel's sons returned very late from a wedding celebration and hadn't yet said Shema. They asked their father what to do.

✓

ANSWER: Rabban Gamliel's Ruling

אָמַר לָהֶם: אִם לֹא עָלָה עַמּוּד הַשַּׁחַר חַיָּיבִין אַתֶּם לִקְרוֹת.

"He said to them: If the light of dawn has not yet risen

you are obligated to recite the Shema."

His Answer: Rabban Gamliel told them they should still recite Shema as long as dawn hadn't arrived yet - consistent with his own opinion stated earlier.

📢

STATEMENT: A General Principle

וְלֹא זוֹ בִּלְבַד אָמְרוּ, אֶלָּא כָּל מַה שֶּׁאָמְרוּ חֲכָמִים ״עַד חֲצוֹת״, מִצְוָתָן עַד שֶׁיַּעֲלֶה עַמּוּד הַשַּׁחַר.

"And it is not only in this case

that the [Sages] said “until midnight”

when according to Biblical law the time actually extends until dawn.

Rather, whatever mitzvah the Sages said

may be performed only until midnight,

the time of the mitzvah

actually extends until the light of dawn rises.""

The Principle: This isn't just about Shema! Whenever the Sages set a "midnight" deadline, the actual obligation extends until dawn. The midnight deadline is precautionary.

📜

PROOF: Examples of This Principle

הֶקְטֵר חֲלָבִים וְאֵבָרִים, מִצְוָתָן עַד שֶׁיַּעֲלֶה עַמּוּד הַשַּׁחַר וְכָל הַנֶּאֱכָלִים לְיוֹם אֶחָד, מִצְוָתָן עַד שֶׁיַּעֲלֶה עַמּוּד הַשַּׁחַר.

"In the case of

the burning of the sacrificial fats and limbs,

the time of the mitzvah extends until the light of dawn rises;

and all those sacrifices that may be eaten for only

one day, the time of the mitzvah actually extends until

the light of dawn rises.

"

Proof Examples:

• Burning sacrificial parts on the altar - can be done all night

• Eating sacrifices designated for "one day" - permitted all night

Both extend until dawn, not just midnight

❓

QUESTION: Then Why Say Midnight?

אִם כֵּן, לָמָה אָמְרוּ חֲכָמִים ״עַד חֲצוֹת״

"If so, why did the Sages say regarding these mitzvos that they may be

performed only until midnight?"

The Obvious Question: If the real deadline is dawn, why did the Sages give a midnight deadline? Why not just tell us the truth?

✓

ANSWER: To Distance People from Sin

כְּדֵי לְהַרְחִיק אָדָם מִן הָעֲבֵירָה

"In order to distance a person from sin."

The Reason: The Sages set an earlier deadline as a "safety fence." If people think they have until dawn, they might procrastinate and actually miss it. By saying "midnight," they ensure people do it on time.

🎯 THE WISDOM OF THE SAGES

📜 The Law: Obligation extends until dawn

⬇️

⚠️ The Problem: People might procrastinate

⬇️

🛡️ The Solution: Set deadline at midnight as protective measure

📊 MISHNAH SUMMARY

Main Topic: When to recite evening Shema

Three Opinions on Deadline:

1️⃣ Rabbi Eliezer: End of first watch

2️⃣ Sages: Midnight

3️⃣ Rabban Gamliel: Dawn

Key Teaching: The "midnight" deadline is precautionary - the actual obligation lasts until dawn, but the Sages created an earlier deadline to prevent people from accidentally transgressing.

🔍 GEMARA BEGINS - ANALYZING THE MISHNAH

Note: All translations below are not from Artscroll.

The mishnah translations above are copied directly from artscroll - which includes the bold and regular font

🎬 GEMARA'S OPENING QUESTIONS

❓

QUESTION #1: Where is the Tanna Standing?

תַּנָּא הֵיכָא קָאֵי דְּקָתָנֵי ״מֵאֵימָתַי״?

"Where is the Tanna standing that he teaches 'From when?'"

The Problem: The Mishnah jumps right into asking "From when..." without any introduction or context. What broader topic is it part of? What's the framework?

❓

QUESTION #2: Why Evening First?

וְתוּ: מַאי שְׁנָא דְּתָנֵי בְּעַרְבִית בְּרֵישָׁא? לִתְנֵי דְּשַׁחֲרִית בְּרֵישָׁא!

"And furthermore: Why does it teach the evening [Shema] first? Let it teach the morning [Shema] first!"

The Problem: The day begins in the morning! Why start with the evening Shema instead of the morning Shema? This seems backwards!

💡 The Gemara's Methodology: Notice how the Gemara doesn't accept the Mishnah at face value. It probes: What's the context? Why this order? This analytical approach is the essence of Talmudic study!

✓

ANSWER #1: The Tanna is Following Scripture

תַּנָּא אַקְּרָא קָאֵי, דִּכְתִיב: ״בְּשָׁכְבְּךָ וּבְקוּמֶךָ״

"The Tanna is standing on the verse, as it is written: 'When you lie down and when you arise.'"

The Answer: The Mishnah is based on Deuteronomy 6:7, which mentions lying down (evening) before arising (morning). That's why it discusses evening first! The Mishnah follows the Torah's sequence.

✓

ANSWER: Rephrasing the Mishnah with Context

וְהָכִי קָתָנֵי: זְמַן קְרִיאַת שְׁמַע דִּשְׁכִיבָה אֵימַת? — מִשָּׁעָה שֶׁהַכֹּהֲנִים נִכְנָסִין לֶאֱכוֹל בִּתְרוּמָתָן

"And this is what it teaches: When is the time for reciting the Shema of lying down [evening]? From the time that the Kohanim enter to eat their teruma."

Understanding: When we add the context from the verse, the Mishnah makes perfect sense. It's asking about the "lying down" time mentioned in Scripture. The full question should be understood as: "When is the time for the evening Shema (mentioned as 'when you lie down')?"

🔄 ALTERNATIVE ANSWER

✓

ANSWER #2: Following Creation's Pattern

וְאִי בָּעֵית אֵימָא: יָלֵיף מִבְּרִיָּיתוֹ שֶׁל עוֹלָם, דִּכְתִיב: ״וַיְהִי עֶרֶב וַיְהִי בֹקֶר יוֹם אֶחָד״

"And if you wish, say instead: He learns from the creation of the world, as it is written: 'And there was evening and there was morning, one day.'"

Alternative Explanation: Genesis 1:5 lists evening before morning in describing Creation. The Mishnah follows this divine pattern where the day begins with evening. This is a fundamental concept in Jewish time-reckoning.

TWO ANSWERS TO WHY EVENING COMES FIRST

⬇️

Answer #1

📖 Based on Shema verse

"When you lie down and when you arise"

Lying down (evening) mentioned first

Answer #2

🌍 Based on Creation

"Evening and morning, one day"

Evening precedes morning in creation

🤔 CHALLENGE TO ANSWER #2

🤔

INQUIRY: But Later in the Mishnah...

אִי הָכִי, סֵיפָא דְּקָתָנֵי ״בַּשַּׁחַר מְבָרֵךְ שְׁתַּיִם לְפָנֶיהָ וְאַחַת לְאַחֲרֶיהָ, בָּעֶרֶב מְבָרֵךְ שְׁתַּיִם לְפָנֶיהָ וּשְׁתַּיִם לְאַחֲרֶיהָ״, לִתְנֵי דְּעַרְבִית בְּרֵישָׁא!

"If so, [regarding] the latter part which teaches: 'In the morning one recites two blessings before it and one after it; in the evening one recites two blessings before it and two after it' - let it teach evening first!"

The Problem: Later in the same Mishnah (which discusses blessings around Shema), morning is mentioned first! If we're following Creation's pattern of evening-then-morning, why switch the order there? This creates an inconsistency!

✓

ANSWER: The Tanna's Teaching Method

תַּנָּא פָּתַח בְּעַרְבִית, וַהֲדַר תָּנֵי בְּשַׁחֲרִית, עַד דְּקָאֵי בְּשַׁחֲרִית, פָּרֵישׁ מִילֵּי דְשַׁחֲרִית, וַהֲדַר פָּרֵישׁ מִילֵּי דְעַרְבִית

"The Tanna opened with evening, then taught morning; while he was dealing with morning, he explained the matters of morning, and then he explained the matters of evening."

Resolution: It's a teaching technique! The sequence is:

1️⃣ Start with evening Shema (following the verse/creation)

2️⃣ Then mention morning Shema

3️⃣ While on the topic of morning, explain its blessings

4️⃣ Then go back to explain evening's blessings

This is practical organization for teaching, not a contradiction to the creation principle.

⏰ ANALYZING THE TIMING: "From When Kohanim Enter"

📢

STATEMENT: The Gemara Quotes the Mishnah

אָמַר מָר מִשָּׁעָה שֶׁהַכֹּהֲנִים נִכְנָסִים לֶאֱכוֹל בִּתְרוּמָתָן

"The Master said: 'From the time that the Kohanim enter to eat their teruma.'"

Setting Up the Discussion: The Gemara now focuses on the Mishnah's specific wording about when Kohanim eat teruma.

❓

QUESTION: Why Not Say the Actual Time?

מִכְּדִי כֹּהֲנִים אֵימַת קָא אָכְלִי תְּרוּמָה? — מִשְּׁעַת צֵאת הַכּוֹכָבִים, לִתְנֵי: ״מִשְּׁעַת צֵאת הַכּוֹכָבִים״!

"Now when do Kohanim eat teruma? From the time of the emergence of the stars. Let it teach: 'From the time of the emergence of the stars!'"

The Question: If the Mishnah means when stars emerge (nightfall), why use this roundabout expression about Kohanim eating? Just say directly: "from when the stars come out!" Why the indirect language?

🎯 THE GEMARA WILL REVEAL: TWO LESSONS IN ONE STATEMENT!

⬇️

✓

ANSWER #1: Teaching in Passing - When Kohanim Eat

מִלְּתָא אַגַּב אוֹרְחֵיהּ קָמַשְׁמַע לַן — כֹּהֲנִים אֵימַת קָא אָכְלִי בִּתְרוּמָה — מִשְּׁעַת צֵאת הַכּוֹכָבִים

"He teaches us a matter in passing - when do Kohanim eat teruma? From the time of the emergence of the stars."

First Lesson: The Mishnah is elegant! It accomplishes two things at once:

Primary Message: When to recite evening Shema

Side Teaching: When Kohanim may begin eating teruma - at nightfall (stars emerge)

By using this expression, the Mishnah teaches both laws simultaneously.

✓

ANSWER #2: And Another Important Teaching!

וְהָא קָמַשְׁמַע לַן דְּכַפָּרָה לָא מְעַכְּבָא

"And this teaches us that atonement does not prevent [eating teruma]."

Second Lesson (more subtle): A Kohen who became ritually impure and then immersed in a mikvah doesn't need to wait until the next day to bring his atonement offering. He can eat teruma that very evening when the stars emerge!

The Law: Immersion + nightfall = permitted to eat teruma

Not Required: Waiting for the next day's sacrifice

🎓 THREE TEACHINGS FROM ONE PHRASE!

Lesson #1: When to recite evening Shema (stars emerge)

Lesson #2: When Kohanim eat teruma (stars emerge)

Lesson #3: Atonement offering not required before eating teruma

📜 SCRIPTURAL ANALYSIS: What Does "The Sun Came" Mean?

📜

PROOF: Proof from a Baraita

כִּדְתַנְיָא: ״וּבָא הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ וְטָהֵר״ — בִּיאַת שִׁמְשׁוֹ מְעַכַּבְתּוֹ מִלֶּאֱכוֹל בִּתְרוּמָה, וְאֵין כַּפָּרָתוֹ מְעַכַּבְתּוֹ מִלֶּאֱכוֹל בִּתְרוּמָה

"As it was taught [in a Baraita]: 'And the sun came and he became pure' - the coming of his sun prevents him from eating teruma, but his atonement does not prevent him from eating teruma."

The Source: The verse in Leviticus 22:7 states that a Kohen becomes pure when "the sun came." The Baraita interprets this to mean:

✓ He must wait for sunset (stars emerging)

✗ He doesn't need to wait for tomorrow's atonement offering

This supports what we just learned about Kohanim eating teruma.

🔍 NOW THE GEMARA ANALYZES THE VERSE ITSELF:

This is classic Gemara! Not satisfied with just citing the verse, it examines what the words actually mean. The phrase could be understood in different ways.

❓

QUESTION: Two Possible Interpretations of the Verse

וּמִמַּאי דְּהַאי ״וּבָא הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ״ בִּיאַת הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ, וְהַאי ״וְטָהֵר״ — טְהַר יוֹמָא. דִּילְמָא בִּיאַת אוֹרוֹ הוּא, וּמַאי ״וְטָהֵר״ — טְהַר גַּבְרָא?!

"From where [do we know] that 'and the sun came' means the sunset, and 'and he became pure' means the day became pure? Perhaps it means the coming of its light [sunrise], and what is 'and he became pure'? The man became pure!"

The Challenge: The Hebrew phrase "uva hashemesh" (the sun came) is ambiguous!

Interpretation A (our understanding):

• "Sun came" = sun-SET (sun goes away)

• "Became pure" = the DAY ended/became pure

• Result: Can eat teruma at nightfall

Interpretation B (alternative):

• "Sun came" = sun-RISE (sun's light arrives)

• "Became pure" = the MAN became pure

• Result: Must wait until morning after bringing sacrifice

🎭 THE VERSE "וּבָא הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ וְטָהֵר" CAN BE READ TWO WAYS!

| Reading #1 (Sunset) |

Reading #2 (Sunrise) |

🌅 "And the sun came"

= Sun departed (sunset)

✨ "And became pure"

= The day ended/cleared

⏰ When can he eat?

That very night (stars emerge)

📋 Sacrifice needed?

No - can eat before bringing it

|

🌄 "And the sun came"

= Sun's light arrived (sunrise)

👤 "And became pure"

= The man became pure

⏰ When can he eat?

Next morning (after dawn)

📋 Sacrifice needed?

Yes - must bring offering first

|

✓

ANSWER: Rabbah bar Rav Sheila's Grammatical Proof

אָמַר רַבָּהּ בַּר רַב שֵׁילָא: אִם כֵּן, לֵימָא קְרָא: ״וְיִטְהָר״, מַאי ״וְטָהֵר״ — טְהַר יוֹמָא

"Rabbah bar Rav Sheila said: If so, let the verse say 'v'yithar' [and he shall become pure]. What is 'v'taher'? [It means] the day became pure."

The Grammatical Argument:

📖 If the verse meant "the man becomes pure":

It would use the verb form "וְיִטְהָר" (v'yithar) - future tense with the letter yud, clearly referring to a person becoming pure

📖 But the verse actually says:

"וְטָהֵר" (v'taher) - past tense form, which suggests a state of purity/clarity being achieved

💡 Therefore:

This form is best understood as "the day became pure/clear" - meaning the day ended and night arrived. It's about the time of day, not the person's status.

📜

PROOF: Folk Saying as Supporting Evidence

כִּדְאָמְרִי אִינָשֵׁי: ״אִיעֲרַב שִׁמְשָׁא וְאִדַּכִּי יוֹמָא״

"As people say: 'The sun has set and the day has become clear.'"

Supporting Evidence from Common Speech:

This is a common Aramaic folk expression used when evening arrives. People would say "the sun set and the day became clear/pure."

Why this matters: This proves that the word "became pure/clear" (טהר/דכי) can naturally refer to the day ending, not just to a person becoming pure. The Torah is using language consistent with how people actually speak!

🎯 PROOF STRUCTURE: How We Know It Means Sunset

❓ Question: Does "sun came" mean sunset or sunrise?

⬇️

💡 Answer: Grammatical analysis - the verb form indicates "day became pure" not "man became pure"

⬇️

📜 Support: Folk expression confirms that "became pure" can refer to day ending

⬇️

🎯 Conclusion: "Sun came" = sunset; Kohanim eat at nightfall without waiting for sacrifice

🌍 MEANWHILE, IN ERETZ YISRAEL...

📢

STATEMENT: A Parallel Discussion

בְּמַעֲרָבָא, הָא דְּרַבָּהּ בַּר רַב שֵׁילָא לָא שְׁמִיעַ לְהוּ, וּבְעוֹ לַהּ מִיבַּעְיָא

"In the West [Eretz Yisrael], this [answer] of Rabbah bar Rav Sheila was not heard by them, and they raised it as a question..."

Historical Context: The Gemara now tells us about scholars in Eretz Yisrael (called "the West" from Babylonia's perspective). They independently struggled with this same verse interpretation, not having heard about the Babylonian solution!

This shows us how the same Torah questions were being examined simultaneously in different Jewish centers.

❓

QUESTION: They Asked the Same Question

הַאי ״וּבָא הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ״ בִּיאַת שִׁמְשׁוֹ הוּא, וּמַאי ״וְטָהֵר״ — טְהַר יוֹמָא, אוֹ דִילְמָא בִּיאַת אוֹרוֹ הוּא, וּמַאי ״וְטָהֵר״ — טְהַר גַּבְרָא

"[They asked:] Is 'and the sun came' the sunset, and 'and he became pure' means the day became pure? Or perhaps it's the coming of its light, and 'and he became pure' means the man became pure?"

The Same Dilemma: The scholars in Israel posed the identical question - does the verse refer to sunset or sunrise? This wasn't yet resolved for them.

✓

ANSWER: They Resolve It from a Baraita

וַהֲדַר פָּשְׁטוּ לַהּ מִבָּרַיְיתָא. מִדְּקָתָנֵי בְּבָרַיְיתָא, סִימָן לַדָּבָר — צֵאת הַכּוֹכָבִים. שְׁמַע מִינַּהּ — בִּיאַת שִׁמְשׁוֹ הוּא, וּמַאי ״וְטָהֵר״ — טְהַר יוֹמָא

"And then they resolved it from a Baraita: Since it teaches in a Baraita, 'A sign for this matter is the emergence of the stars' - learn from this that it is the sunset, and 'and he became pure' means the day became pure."

Their Solution (Different from Babylonia's):

Instead of using grammatical analysis, the scholars in Israel found a Baraita (an external teaching) that explicitly states:

"A sign for this matter is the emergence of the stars"

This Baraita clearly indicates that when Kohanim can eat teruma, it's at nightfall (when stars emerge), not at sunrise. Therefore, "the sun came" must refer to sunset!

Two different proofs, same conclusion:

🇮🇶 Babylonia: Grammatical analysis

🇮🇱 Israel: Explicit Baraita

📢

STATEMENT: Final Conclusion Reached

Final Understanding Achieved:

✅ "And the sun came" = sunset (NOT sunrise)

✅ "And became pure" = the day ended (NOT referring to the man)

✅ Kohanim can eat teruma = at nightfall when stars emerge

✅ Atonement offering = NOT required before eating teruma

✅ Evening Shema = also begins at this time (when stars emerge)

Multiple Proofs Converge:

• Grammatical analysis (Babylonia)

• Folk expressions

• Explicit Baraita (Israel)

All lead to the same conclusion!

🌍 TWO CENTERS OF LEARNING, ONE TRUTH

🇮🇶 BABYLONIA

Scholar: Rabbah bar Rav Sheila

Method: Grammatical analysis of verb forms

Proof: "וְטָהֵר" (v'taher) indicates day became pure

Support: Folk saying about sunset

🇮🇱 ERETZ YISRAEL

Scholars: The sages of the West

Method: External source (Baraita)

Proof: Baraita explicitly says "stars emerge"

Support: Direct textual evidence

⬇️ BOTH ARRIVE AT THE SAME CONCLUSION ⬇️

Sunset = time for eating teruma = time for evening Shema

📊 COMPREHENSIVE SUMMARY OF THE ENTIRE AMUD

🎓 What We Learned Through This Discussion:

📋 THE MISHNAH TAUGHT US:

- Three opinions on when evening Shema's deadline ends (first watch, midnight, or dawn)

- All agree it begins when Kohanim eat teruma (stars emerge)

- A story illustrating Rabban Gamliel's lenient view

- A principle: "Midnight" deadlines are precautionary - actual obligation extends to dawn

- The reason: To distance people from accidental transgression

🔍 THE GEMARA ANALYZED:

- Context Questions: Why does the Mishnah start abruptly? Why evening before morning?

- Two Answers: Following Scripture's "when you lie down" OR following Creation's "evening and morning"

- Teaching Method: Why the order changes later in the Mishnah (practical pedagogy)

- Efficient Language: The Mishnah teaches multiple lessons through one expression about Kohanim

- Scriptural Deep-Dive: What does "the sun came and he became pure" really mean?

- Grammatical Proof: The verb form reveals it's about day ending, not man being purified

- Cultural Evidence: Folk sayings support this interpretation

- Parallel Learning: Same questions independently arose in Babylonia and Israel

- Multiple Proofs: Different methods (grammar vs. Baraita) reaching the same truth

💡 KEY TAKEAWAYS FROM THIS AMUD

🎯 About Gemara Study:

The Gemara doesn't just accept statements - it probes, questions, analyzes, and supports every claim with logic and sources. Notice how each question leads to deeper understanding, and how multiple scholars across different regions grappled with the same issues. This is the beauty of Torah study: a multi-generational, geographically dispersed conversation seeking truth!

📚 The Logical Flow:

Every step follows a pattern: Questions receive Answers. Inquiries challenge existing proofs. Statements present information. Proofs support claims. Learning to identify these steps is the key to understanding Gemara!

🌟 The Practical Result:

From all this analysis, we learn the practical law: Evening Shema begins at nightfall (when stars emerge, the same time Kohanim may eat teruma after immersion). While the Sages set midnight as a precautionary deadline, the actual obligation extends until dawn - giving us insight into both the law and the wisdom behind rabbinic safeguards.

🔗 The Unity of Torah:

Notice how one topic (Shema timing) leads us to explore laws about Kohanim and teruma, scriptural interpretation, grammatical analysis, folk wisdom, and even the order of Creation itself. Everything in Torah is interconnected - studying one area illuminates others!

🎓 MASTERING THE GEMARA'S LANGUAGE

Understanding these terms helps you follow any Gemara discussion:

📢 Statement

A declaration or presentation of information

❓ Question

A request for information or clarification

✓ Answer

The response to a question

🤔 Inquiry

A challenge or critical examination

📜 Proof

Evidence or support for a claim

📖 How to Use This Breakdown for Learning

- First Pass: Read through once to get the overall flow - don't worry if you don't understand everything

- Second Pass: Focus on identifying the logical steps - find each Question, Answer, Inquiry, and Proof

- Third Pass: Try to understand WHY each question was asked and what makes each answer satisfying

- Fourth Pass: Look at the Hebrew text and see if you can identify key words that signal logical transitions

- Practice: Try explaining one section to a study partner using your own words

- Apply: Use this same analytical approach when learning new Gemara texts

🎊 Congratulations!

You've completed a full analysis of Berachot 2a!

You've seen how the Gemara analyzes a Mishnah from every angle,

how it uses grammar, logic, and external sources to build understanding,

and how scholars in different lands wrestled with the same questions.

This is the foundation of Talmudic study.

Keep learning, keep questioning, and keep growing! 📚✨